In a previous analysis I gave some context for what is generally contained in DATCP’s annual Nutrient Management Update and provided some general critiques of the form and content of the update. In this analysis, I will focus on one specific data point in the 2020 Nutrient Management Update: the 2020 plan acreage change compared to 2019 (shown in Figure 1 above). I’ll divide this analysis up into three sections: 1. why this data point is of particular interest 2. methods of data collection and analysis and 3. conclusions.

The Data

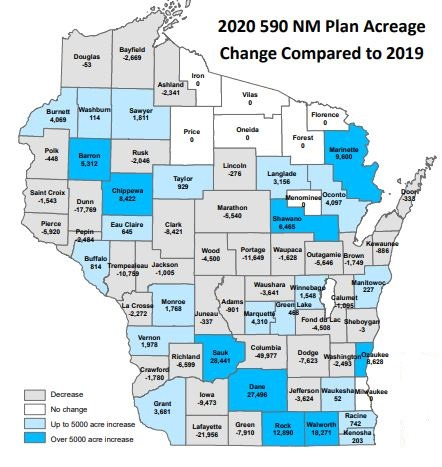

In a report with some very poor data visualizations, Figure 1 really pops out at you. All of the grey colored counties lost NMP acres from 2019 to 2020. With just a quick glance, it is clear that well over 50% of counties saw a decrease in NMP acres. Acre decreases range from 3 acres to 49,977 acres. The update doesn’t offer any real analysis to indicate why we saw this change. Further complicating this is the fact that DATCP changed the way they report acres in the 2020 update. In this update, DATCP took CAFO NMP acres out of the total county acre count. This was a necessary thing to do because some acres are accounted for in a individual farm NMP as well as a CAFO NMP that has a manure agreement with that individual farm. Leaving in the CAFO acres resulted in double counting some areas, and make it seem like the percentage of cropland in NMP was higher than it actually was.

This causes confusion for the reader because there are actually two factors leading to a decrease in reported NMP acres: 1. leaving out CAFO acres and 2. the “mystery” factor. In my research, I found that some readers attributed the entire acre decrease to the CAFO factor. This is understandable based on the way the data is presented. The CAFO acre decrease is pretty well explained and there are data visualizations and text that clearly show how removing the CAFO acres is affecting the count. The “mystery” factor isn’t accounted for at all. The only analysis we get is buried in the caption of Figure 1 (Figure 6 in the DATCP report), where they say “The extent of the impacts of COVID 19 or other factors, and their role in the decline between 2019 and 2020, on NM planning and reporting are unknown (for example, plans were unable to be updated or there was accelerated loss of farms).”

In sum, we are faced with some potentially very troubling data in terms of a significant decrease in NMP acres across the state. The DATCP report not only does not clearly address potential reasons for this decrease, but it also includes confounding data in the removal of CAFO acres that makes it impossible to get a real handle on what the real trend in NMP acres is. To investigate I sent emails to the DATCP staffer who is listed as a contact in the report and the county conservationists in counties with particularly high NMP acre decreases.

The Analysis

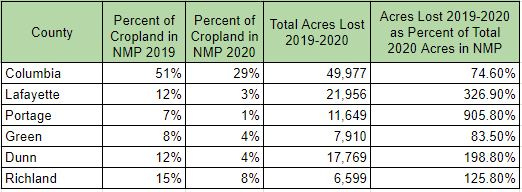

Figure 2 shows data from the counties considered in this analysis. While high NMP acre decrease was the main criteria for inclusion in this analysis, these counties are also spread throughout the state and represent a range of agricultural systems and ecosystems within which agriculture operates.

When I reached out to the county conservationists, I noted the specific acre decrease for their county and I added the comment that it was an extreme decrease. I also noted that, while most counties saw acre decreases, their counties were on the high end. I ended my note by asking if their office has provided any interpretation for the data.

I got a range of responses. A third of county staff responding (2 out of 6) reported to me that the decrease was due to DATCP removing CAFO acres. This is not accurate, but it is clear to see that the misunderstanding is due to the way the data was presented in the DATCP report. Another third of county staff responding reported that the data was off because they don’t collect NMPs from every operation every year. It makes sense that this would result in widely varying reported acres from year to year. One county staffer responded that nobody in the office was involved in the reporting to DATCP, so could offer no interpretation. One county staffer responded that not holding a training course for NMP resulted in fewer submissions and also noted that they had a hard time getting responsible parties to turn in plans despite reaching out.

As a whole, this is a very disappointing result from the counties. County staff from Green and Dunn counties both offered objectively false interpretations of the data when they attributed the decrease to the way CAFO acres are included. I have no reason to indicate that this obfuscation is deliberate, but it is clearly problematic.

County staff from Portage and Columbia counties both indicated that the issue was due to the fact that NMPs are not required to be submitted annually in those counties. The law states that NMPs must be submitted every four years, and these counties are only requiring the minimum. Even if every four years is technically allowable, it isn’t adequate. Plans are supposed to be updated whenever there is a change. I know of no farms that plan out exactly what their cropping practices will be four years from now. Even if they have a sincere desire to stick to the plan, weather is almost certainly going to force them to change something at some point. Successful NMP implementation requires a strong relationship between the landowner/farmer and plan writer. At minimum these two parties would have to meet annually to go over changes, and these changes should be reported to the county. When I was writing plans I would sometimes provide multiple plan updates per year for individual farms. In a fully functioning NMP system, annual updates are necessary. Not only does this clean up data collection problems, it also has the potential to increase NMP implementation due to increased communication between landowner/farmer and plan writer. Within this category there was a range of responses. The county staffer from Columbia County provided a detailed explanation of why collecting plans every four years presents a data challenge, and provided a alternative data set that showed much more consistent NMP acreage across years. They also indicated that they are working with the state to improve how they report NMP acres to provide more clear data in the future. The county staffer from Portage County provided only a brief response in which they assured me that “anecdotally” there are more acres in NMP in the county than the DATCP report suggests. While this may well be the case, it provides no information for the public to verify the statement.

Staffing turnover is a major issue in nutrient management planning generally and the county land and water conservation offices specifically. The response from Lafayette County illustrates this. The county staffer that responded indicated that nobody in the department was involved in the reporting last year so they couldn’t provide any interpretation. While this is likely true, it is simply unacceptable. Loss of institutional memory resulting from high staff turnover prevents us from knowing where we stand in relation to the past and from learning lessons from the mistakes of the past. It also makes it nearly impossible for the public to engage with these topics.

The response from the Richland County staffer indicated two issues: 1. not holding farmer trainer classes and 2. reluctance of landowners/farmers and plan writers to turn in plans despite prompting from the county. The lack of training classes could be more significant than my (admittedly limited) data set indicates. There are two categories of people who can write plans: 1. a certified plan writer and 2. a landowner/farmer with the proper training credentials. The majority of plans are written by certified professional plan writers. This group maintains certification through continuing education requirements. Landowners can write the plan for land that they own and farm, but they must have the proper training. This includes an intensive upfront training to get the NMP set up and continuing education requirements to maintain certification. If trainings that were required were not held, it could result in some plans not being able to be turned in. In order to verify this, you’d have to dig into the data to see what plans were landowner/farmer written plans. The communication from the county staffer provides no information to determine how much of the decrease can be attributed to this factor. The other part of the county staffer’s response gets us closer to the truth, but doesn’t allow us to draw any firm conclusions. They said that they had a “hard time” getting landowners/farmers and plan writers to submit plans despite making calls to try to solicit more submissions. The question of why they had a hard time is key here. I can say from personal experience working on NMPs from across the state that landowners/farmers don’t hold themselves accountable for following these rules and laws. This has always caused conflict, and as we get closer to actually implementing NMPs that conflict is necessarily going to increase.

I posed the same question to the DATCP staffer listed as a contact on the report. They indicated that while it is too early to say that 2020 represents a trend in declining NMP acres, the state has clearly seen a plateau in recent years. This is a frank admission that the NMP program has a big problem. DATCP has been tasked with increasing NMP acres, and they are clearly not achieving that goal. The staffer also noted that they are in the process of doing strategic planning to address the problems of low NMP adoption, understanding, and implementation.

Conclusions

The DATCP staffer is clearly right: this data set doesn’t support the conclusion that the NMP acre decrease in 2020 represents a trend. It is clear, however, that the NMP program is in crisis. The year this report came out is the same year I left my role as a plan writer. I first got interested in plan writing back in 2014 when I was a paralegal intern at the DNR Bureau of Legal Services. While there I was involved in the a contested case hearing for a CAFO in northeast Wisconsin. From there I went on to school at Fox Valley Technical College where I learned the agronomy trade and how to write plans. From there I got my start writing actual plans at a midsize independent ag retailer in northeast Wisconsin. Next I moved down to the Madison area where I started writing plans for the one of the two major private soil testing labs in the state. The soil testing lab had a contract to write all of the plans for one of the biggest co-ops in southern Wisconsin, and I wrote all of the plans. I was prevented from doing my job because landowners/farmers refused to provide the necessary information. Without this information, I couldn’t determine if the operation was incompliance. When I brought these concerns to management at the soil lab they made it very clear: your job is data entry. Even if the information is obviously false or incomplete, the landowner/farmer is paying for the plan so I was supposed to just do whatever they said. Soil testing lab management stated explicitly that being aggressive about producing compliant plans could hurt profit in other parts of the business. With this guidance, it became clear that staying in my role would make me complicit in these frauds and abuses. So I walked away.

In this context, we don’t need to see a statistically significant downward trend to describe the NMP program as in crisis. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of rainfall events during the times of year when row crop fields are most susceptible to severe erosion. Lakes and streams across the state are unusable for recreation due to poor agricultural practices. Urban municipalities are forced to remove nitrates from drinking water at great expense to make it safe. States and counties point to NMP as the main tool for addressing water quality issues, but they can’t answer basic questions about the program. If the NMP process had been adequately integrated into the crop planning process, a disruption like the pandemic wouldn’t be so harmful to the NMP program. Nobody is claiming that these acres didn’t get planted. We just know that the risks of nutrients leaving the field weren’t planned for through the NMP process.

Some points to go forward:

Greater collaboration between the state and counties in reporting NMP acres is necessary.

The state needs to improve the data presentation and analysis in the Nutrient Management Updates so that it is accessible to a non-specialist audience.

County conservation staff need to have a better handle on trends in enrolled NMP acres in their counties.

High turnover in county conservation departments prevents adequate implementation of NMP.

Submitting NMPs to the county should be required annually to facilitate better data reporting and NMP implementation.

There needs to be real consequences for landowners/farmers who fail to comply with the rules. Landowners/farmers are currently acting with impunity due to lack of enforcement.

Organizational forms that provide effective oversight are necessary. Right now oversight primarily comes from groups and individuals with a stake in the current system.